Lambeth Palace

Eight centuries of ecclesiastical power where the Church and Crown converge on the Thames

The official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury for over 800 years, Lambeth Palace stands as a masterpiece of medieval and Tudor architecture on the south bank of the Thames. This historic landmark has witnessed pivotal moments in English religious and political history, from the English Reformation to the English Civil War. Recently restored with a £40 million renovation, the palace combines its role as a private residence with a venue for state occasions and ecclesiastical gatherings, housing museum-quality artefacts and featuring iconic structures like Morton's Tower and the 13th-century chapel.

A brief summary to Lambeth Palace

- London, SE1 7JU, GB

- +442078981200

- Visit website

- Duration: 0.5 to 2 hours

- Free

-

Outdoor

- Mobile reception: 5 out of 5

Local tips

- The palace is not open to the general public for regular tours, but guided visits can occasionally be arranged through the official website or during special heritage events. Check ahead for open days and special access opportunities.

- The adjacent Garden Museum, housed in the 18th-century Church of St Mary-at-Lambeth and its courtyard, offers public access and provides excellent context for understanding the palace's historical significance and its relationship to the surrounding area.

- Morton's Tower, the distinctive red-brick Tudor gatehouse, is visible from the street and represents one of London's finest examples of early Tudor architecture. The exterior can be appreciated from the public realm without requiring palace access.

- Visit during spring or summer when the palace grounds are occasionally opened for special events, heritage celebrations, or the Lambeth Conference, which occurs approximately every ten years.

- The Thames Path offers excellent views of the palace's riverside elevation and provides context for understanding its historical importance as a water-accessible residence for archbishops and dignitaries.

For the on-the-go comforts that matter to you

- Information Boards

- Seating Areas

Getting There

-

London Underground and Walking

From Waterloo Station (served by the Bakerloo, Northern, Jubilee, and Southern lines), exit and follow signs toward the Thames. Walk south across Waterloo Bridge or use the riverside path; the palace is approximately 10–15 minutes on foot from the station. The entrance is on Lambeth Palace Road, clearly signposted. This is the most direct public transport option with frequent service throughout the day.

-

Bus Service

Multiple bus routes serve the area around Lambeth Palace, including routes 77, 87, 344, and 507, which stop on or near Lambeth Palace Road. Journey times from central London vary between 15–30 minutes depending on traffic and starting point. Buses run frequently throughout the day and evening, making this a reliable option during peak hours when the Underground may be crowded.

-

Thames Riverboat

Seasonal river services operate from Westminster Pier and other central London piers. The journey takes approximately 10–15 minutes and provides a scenic approach to the palace via the Thames. Services typically run March through November, with reduced frequency in winter months. This option offers a unique perspective on the palace's historical riverside location and is particularly atmospheric during summer months.

-

Taxi or Ride-Share

Taxis and ride-share services (Uber, Bolt) can deliver you directly to Lambeth Palace Road. Journey times from central London typically range from 10–25 minutes depending on traffic conditions. Parking near the palace is extremely limited due to its location in central London; ride-share services are more practical than private vehicles. Fares vary but expect £8–20 from central locations.

Lambeth Palace location weather suitability

-

Any Weather

Discover more about Lambeth Palace

Eight Centuries of Ecclesiastical Power and Influence

Lambeth Palace has served as the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury since approximately 1200, making it one of England's most historically significant yet often overlooked landmarks. The palace's location on the south bank of the Thames, directly opposite Westminster Palace, was deliberately chosen to reflect the close relationship between the Church and the Crown. During the medieval period, the Archbishop of Canterbury held one of the most powerful positions in the realm, often serving as the monarch's chief councillor and Chancellor of England. The proximity of the two palaces across the river symbolised the balance of spiritual and temporal authority that defined medieval English governance. The name Lambeth itself derives from its first recorded mention in 1062 as 'Lambehitha', meaning 'landing place for lambs', reflecting its historical importance as a river port where archbishops and other dignitaries could arrive by water. This Thames-side location proved crucial throughout the palace's history, allowing the archbishops to maintain their political influence at the heart of English power.Architectural Evolution from Medieval Chapel to Tudor Gatehouse

The earliest structures at Lambeth Palace date to the early 13th century, when Archbishop Stephen Langton commissioned the construction of a small palace complex that included private apartments, a chapel, and a great hall. The Gothic chapel and crypt, built around 1200, rank among London's oldest surviving buildings. The chapel became particularly significant in Anglican history, serving as the site where numerous bishops were consecrated. Archbishop Morton installed the original stained-glass windows in 1496, depicting the biblical narrative from creation to the Last Judgement—windows that would later be controversially replaced by Archbishop Laud in 1634. The most iconic structure at Lambeth Palace is Morton's Tower, the magnificent five-storey red-brick Tudor gatehouse completed in 1495 by Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop and Lord Chancellor under Henry VII. This castle-like structure originally served as a porter's lodge, prison, and accommodation for senior household members. From the tower's upper levels, bread, broth, and money were distributed to the poor and needy. The tower's distinctive Tudor brickwork represents one of London's finest examples of early Tudor construction. Another notable structure is Lollards' Tower, built in the 15th century between the chapel and the river. Originally constructed as a water tower, it became infamous as a prison where followers of John Wycliffe—the theologian whose radical ideas challenged Church corruption—were incarcerated. Archbishop Chichele, who built the tower, showed unusual mercy by having heretics whipped rather than burned at the stake, a practice common elsewhere.The Reformation and Henry VIII's Influence

During the 16th century, Lambeth Palace became central to the English Reformation under Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. Cranmer, the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury, transformed the palace into a centre of religious reform. He produced two prayer books that became the foundation for the Book of Common Prayer, fundamentally altering English religious practice. Henry VIII was a frequent visitor to Lambeth Palace, renowned for its hospitality, and Cranmer expanded the palace staff from sixty to one hundred to accommodate royal visits. The archbishop added private chambers and a long gallery modelled on Henry VIII's own residences, though most of these additions were demolished in the 19th century. The palace's chapel underwent significant changes during this period. Archbishop Laud, serving in the early 17th century, richly decorated the chapel and replaced Morton's original stained-glass windows in 1634, a controversial decision that reflected the theological tensions of the era. Laud's tenure proved turbulent; in May 1640, an angry mob of 500 London apprentices attacked the palace, seeking to capture the archbishop due to popular discontent with his Arminianist theology.Destruction, Restoration, and Victorian Transformation

The English Civil War inflicted severe damage on Lambeth Palace. Between 1642 and 1660, Parliamentarian soldiers occupied the complex, and Cromwellian forces ransacked and partially demolished the buildings. The great hall was demolished entirely, its materials sold off. The chapel was damaged, and Archbishop Parker's tomb was desecrated, his remains thrown onto a dung heap in the stable yard. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Archbishop William Juxon undertook major reconstruction, completely rebuilding the great hall in 1663 with a late Gothic hammerbeam roof—a choice that served as a visual statement of continuity with the Old Faith and the end of the Interregnum. Samuel Pepys famously described it as 'a new old-fashioned hall'. In the 19th century, architect Edward Blore (who later rebuilt Buckingham Palace) undertook extensive renovations between 1829 and 1834. Blore's neo-Gothic additions included large extensions to house the archbishop, allowing the original medieval buildings to be converted into the archdiocese's library, record office, and secretariat. These additions fronted a spacious quadrangle and significantly expanded the palace's capacity to serve both as a residence and administrative centre.Modern Heritage and Contemporary Restoration

Lambeth Palace remains one of the most important heritage buildings in the British Isles, containing museum-quality artefacts and serving dual roles as the archbishop's personal residence and a venue for intimate engagements with world leaders and vast gatherings such as the Lambeth Conference, which brings together bishops from the worldwide Anglican Communion. The palace grounds include the White Marseilles Fig Tree, planted in 1556 by Cardinal Reginald Pole, the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury—one of Britain's most famous trees. A comprehensive £40 million restoration project, completed recently and undertaken by the architectural firm Wright & Wright, has restored and protected the palace's historic features while making it environmentally sustainable. The work involved cleaning 800 square metres of historic stonework, replacing 1,450 square metres of floorboards, and undertaking plastering and painting across more than 13,500 square metres—an area equivalent to two football pitches. The restoration included three air-source heat pumps, rooftop solar panels, and energy-efficient double-glazed windows to reduce the palace's environmental impact. Archaeological discoveries during the restoration, including human remains of potentially Saxon or earlier origin and evidence of medieval cesspits and Tudor-era cloister layouts, have added new layers of understanding to London's ancient history.Iconic landmarks you can’t miss

Southbank House

0.4 km

Historic terracotta landmark in Lambeth, blending Victorian pottery heritage with modern creative workspaces.

Statue of George V

0.6 km

A dignified white Portland stone statue honoring King George V, standing proudly in Westminster’s historic Old Palace Yard.

South Bank Lion

0.6 km

Majestic 1837 Coade stone lion guarding Westminster Bridge, symbolizing London’s resilience and rich heritage.

Statue of Oliver Cromwell

0.6 km

A commanding bronze tribute to Oliver Cromwell, standing outside Westminster Hall as a symbol of Britain’s turbulent 17th-century history and contested legacy.

Westminster Hall

0.6 km

Step into Westminster Hall, a majestic medieval masterpiece that has witnessed a millennium of British history, law, and monarchy.

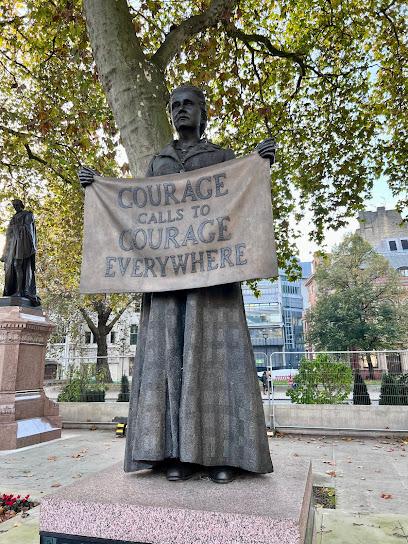

Millicent Garrett Fawcett Statue

0.7 km

Honoring Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the first woman commemorated in Parliament Square, inspiring equality through her iconic statue and legacy.

The London Dungeon

0.8 km

Explore London's haunting history at The London Dungeon, where thrilling rides and live performances bring the city's dark tales to life.

Parliament Sq

0.8 km

Where Britain's democratic institutions converge, history breathes, and voices are heard.

County Hall

0.8 km

Historic Edwardian Baroque landmark on London’s South Bank with iconic river views, cultural venues, and rich civic heritage.

King Charles Street

0.8 km

Explore King Charles Street, a historic London government hub famed for its grand Victorian architecture and pivotal role in British political life.

lastminute.com London Eye

0.8 km

Discover breathtaking views and iconic landmarks from the London Eye, a must-visit attraction on the River Thames.

The Battle of Britain Monument

0.8 km

Explore the Battle of Britain Monument in London, a powerful tribute to the heroism of RAF pilots during World War II, rich in history and artistic elegance.

King Charles Street Arch

0.9 km

A grand 1908 triple-arched gateway in London’s Whitehall, rich in sculptural detail and historical significance.

The Queen's Walk

0.9 km

London's iconic riverside promenade connecting Parliament to Tower Bridge with unparalleled city views.

The Cenotaph

0.9 km

Britain’s national war memorial in Whitehall, a solemn tribute to the fallen of the World Wars and later conflicts.

Unmissable attractions to see

Garden Museum

0.1 km

Medieval church celebrating British gardens, from royal estates to allotments, with seasonal café.

Archbishop's Park

0.3 km

Historic green space in central London with sports, playgrounds, gardens, and a welcoming community atmosphere.

Lambeth Bridge

0.3 km

A vibrant red steel arch bridge blending historic ferry roots, elegant design, and London legends across the Thames.

Tally Ho ~ London Bike Tours, Taxi Tours & Pub Tours

0.3 km

Explore London’s iconic sights and hidden treasures on classic British bicycles with expert guides and lively pub stops.

Victoria Tower Gardens South

0.4 km

A peaceful riverside park in Westminster featuring iconic memorials, scenic views, and a family-friendly playground beside the Houses of Parliament.

Royal Court

0.4 km

London’s Royal Court Theatre: A historic beacon for groundbreaking new plays and emerging playwrights in the heart of Sloane Square.

Tamesis Dock

0.4 km

Experience the lively atmosphere at Tamesis Dock, a floating bar on the Thames, offering drinks, food, and live music with stunning river views.

Florence Nightingale Museum

0.5 km

Explore the inspiring legacy of Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, at this engaging museum in the heart of London’s South Bank.

Sinfonia Smith Square

0.5 km

Experience world-class classical music in a stunning 18th-century Baroque concert hall at the heart of Westminster.

South of the River

0.5 km

A prestigious, fully fitted office building with prime views opposite the Houses of Parliament in London’s thriving South Bank business district.

Memorial wall

0.5 km

A heartfelt 500-metre mural along the Thames commemorating every UK life lost to COVID-19 with over 245,000 hand-painted hearts.

Palace of Westminster

0.5 km

Discover the architectural splendor and historical significance of the Palace of Westminster, the iconic heart of British democracy in London.

Jewel Tower

0.5 km

Discover the Jewel Tower, a medieval fortress guarding royal treasures and parliamentary history opposite London’s iconic Houses of Parliament.

London Bicycle Tour Company

0.5 km

Explore London's landmarks and hidden streets on two wheels with expert local guides and quality bikes.

Westminster Bridge

0.6 km

Experience the historic charm and stunning views from Westminster Bridge, an iconic London landmark linking culture and architecture.

Essential places to dine

Sapori

0.6 km

Enjoy authentic Italian cuisine with generous portions and a lively atmosphere in the heart of Westminster, London.

Osteria dell'Angolo

0.6 km

Classic Italian flavors and fresh pasta in a warm, elegant Westminster setting with attentive service and a visible kitchen.

OKAN South Bank

0.7 km

Experience authentic Osaka-style okonomiyaki and Japanese street food in a cozy, lively South Bank eatery with friendly service and a nostalgic vibe.

Troia Southbank

0.7 km

Experience authentic Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cuisine with halal options in a vibrant riverside setting near the London Eye.

Ma La Sichuan

0.8 km

Experience authentic, boldly spiced Sichuan cuisine in the heart of Westminster with vibrant flavors and a welcoming atmosphere.

Mio Restaurant & Bar

0.9 km

Authentic Italian flavors and warm hospitality await you in this cozy central London gem with generous portions and great value.

The Pem

1.0 km

Elegant modern British dining in Westminster, honoring heritage with exquisite seasonal menus and refined ambiance.

Caxton Grill

1.0 km

Refined British grill cuisine with fresh rooftop garden produce in a relaxed Westminster setting inside St Ermin’s Hotel.

The Archduke

1.1 km

Lively steakhouse and wine bar in Waterloo with superb Scotch beef, classic desserts, and live jazz in a buzzy, inviting atmosphere.

Colosseo Restaurant

1.1 km

Experience authentic Italian flavors and warm hospitality in the heart of London’s Victoria at Colosseo Restaurant.

Ping Pong Southbank

1.1 km

Lively Southbank dim sum and cocktail bar blending traditional Chinese flavors with modern Asian fusion in a bustling riverside setting.

Chez Antoinette Victoria

1.1 km

Authentic French bistro in London’s Victoria offering classic Lyonnais and Parisian dishes in a cozy, Parisian-style setting.

Southbank Centre Food Market

1.1 km

A lively weekend street food market on London’s South Bank offering diverse global cuisines in a vibrant riverside setting.

wagamama southbank

1.1 km

Lively riverside pan-Asian dining with fresh, bold flavors and stunning Thames views at London’s Royal Festival Hall.

Strada Southbank

1.1 km

Authentic Southern Italian flavors served with vibrant riverside views in the heart of London’s Southbank.

Markets, malls and hidden boutiques

Browns of London

0.5 km

Explore Browns of London for unique handcrafted gifts and local treasures in the heart of the city, perfect for memorable souvenirs from your travels.

The Giftree London

0.6 km

Discover London's soul in souvenirs, crafts, and conveniences at this Lambeth gem—unique gifts, luggage storage, and local flair await.

Jubilee Shop (Houses of Parliament Gift Shop)

0.6 km

Discover exclusive British political gifts and souvenirs inside the historic Westminster Hall at the Jubilee Shop, Houses of Parliament.

Westminster Abbey Shop

0.7 km

Discover exclusive Abbey-inspired gifts and souvenirs that support Westminster Abbey’s heritage and conservation efforts.

Houses of Parliament Shop

0.7 km

Discover parliamentary pride in souvenirs, books, and gifts at this cozy Bridge Street boutique, steps from Westminster's iconic halls.

Gift Shop - London Eye Shop

0.8 km

Capture London's magic at the London Eye Gift Shop: exclusive souvenirs, Thames views, and iconic keepsakes from the wheel's base.

Custom Gifts By Jupiter

1.0 km

Unleash creativity with bespoke gifts and custom decor from this South Bank artisan haven near the Thames and iconic landmarks.

Southbank Centre Shop, Mandela Walk

1.1 km

Discover creative gifts, sustainable homewares, and arts-inspired souvenirs on vibrant Mandela Walk, opposite Royal Festival Hall—a stylish treat amid South Bank's cultural heartbeat.

Gifts of London

1.3 km

Discover unique souvenirs and gifts that embody the spirit of London at Gifts of London, your perfect shopping destination.

Crest of London Ltd

1.3 km

Discover authentic London souvenirs and local crafts at Crest of London Ltd, your premier gift shop in historic Whitehall.

Cardinal Place

1.5 km

Experience the ultimate shopping and dining destination at Cardinal Place, London’s vibrant commercial hub near Victoria Station.

Sugar And Style

1.5 km

Discover design-led fashion accessories in Gabriel's Wharf, London's arty South Bank riverside haven blending style, creativity, and Thames views.

j-me original design ltd

1.6 km

Whimsical designs with a humorous twist from London's Oxo Tower creative hub – quirky home gifts blending fun, function, and British ingenuity.

Brand Academy Independent Gift Shop

1.6 km

Dive into a world of whimsical designs and unique finds at this South Bank gem, where global brands meet emerging talents in the heart of Oxo Tower Wharf.

SUCK UK Alternative Gifts (OXO Tower)

1.6 km

Discover quirky, clever gifts and homewares at SUCK UK’s flagship store in London’s iconic OXO Tower.

Essential bars & hidden hideouts

Primo Bar, London

0.6 km

Sophisticated South Bank cocktails and live jazz with Big Ben views—Primo Bar blends daytime lounge ease with electrifying nightly performances in stylish 60s-inspired surrounds.

Waterloo Lost Property Office Speakeasy

0.8 km

Discover a hidden 1920s-inspired speakeasy in Waterloo serving expertly crafted cocktails in a seductive, vintage setting.

All Bar One Waterloo

0.8 km

Sophisticated South Bank bar serving creative cocktails, sharing plates, and wines in a lively spot near Waterloo Station and the London Eye.

Slug & Lettuce - County Hall

0.8 km

Chic South Bank cocktail haven in County Hall: bottomless brunches, 2-for-1 sips, pub classics, and Thames views for London's liveliest lunches and nights out.

The Red Lion, Parliament Street

0.8 km

A venerable Westminster corner pub — late‑Victorian fittings, political atmosphere and a long history beside Downing Street and Parliament.

Le Champagne Bar

0.8 km

A compact riverside champagne lounge beside the London Eye—perfect for a celebratory flute and framed Thames views.

Bar @ 26 Leake Street

0.8 km

Experience London’s vibrant street art and nightlife culture at 26 Leake Street, a unique cocktail bar and event venue in Waterloo’s iconic graffiti tunnels.

Westminster Arms

0.9 km

Historic Westminster pub with parliamentary division bell, Shepherd Neame ales, and cozy alcoves steps from Abbey and Parliament—timeless British charm in political heart.

Morpeth Arms

0.9 km

Historic Thameside pub with cask ales, hearty fare, haunted cellars, and MI6 views— a Westminster gem blending Victorian ghosts and modern cheer.

Blue Boar Pub

0.9 km

Traditional Westminster pub serving hearty British classics in a cozy, historic setting near Abbey and Parliament—perfect for ales, roasts, and relaxed evenings.

Two Chairmen

1.0 km

Traditional Westminster pub serving hearty pies, fresh ales, and classic British cheer just steps from St. James's Park and Parliament.

The Thirsty Farrier Cocktail Bar

1.0 km

A vibrant London cocktail bar offering expertly crafted seasonal drinks with scenic riverside views and a welcoming atmosphere.

honestfolk Cocktail Bar (Southbank Centre Food Market)

1.1 km

Seasonal cocktails and classics from a cozy mobile bar at Southbank Centre Food Market, where Thames breezes mingle with market buzz and craft libations.

Southbank Centre, Members Bar

1.2 km

Elevated wine bar with Thames panoramas and cultured calm atop Royal Festival Hall—perfect for drinks amid London's arts heartbeat.

Adam & Eve

1.2 km

Classic Westminster pub pouring real ales and hearty grub amid historic streets—a cozy haven near Parliament and the Abbey for authentic London pints.

Nightclubs & after hour spots

STRAWBERRY SUNDAE

0.7 km

Retro rave haven in Waterloo Arches: Daytime hardcore beats, 90s DJ legends, and industrial euphoria from midday to midnight.

Cirque Du Soul

0.8 km

Dive into Leake Street's graffiti tunnel for soul-stirring electronic nights at this underground nightclub haven.

We Are Waterloo

0.8 km

Dive into Leake Street's graffiti heart where street art meets thumping beats in London's ultimate underground nightclub haven.

The Boat Show Comedy Club

1.0 km

London’s premier floating comedy club aboard the historic Tattershall Castle, blending laughter with iconic riverside views and vibrant nightlife.

Union

1.0 km

Vauxhall's relentless nightclub heartbeat: techno-fueled nights stretching to dawn in multi-zone bliss along the Thames.

Bootylicious London last Saturday of the month

1.0 km

Late-night Vauxhall institution for raw techno, queer-focused party nights and after-hours clubbing on Albert Embankment.

Lightbox London

1.2 km

Dive into dazzling LED realms at Vauxhall's electrifying nightclub, where lights, beats, and all-night energy create unforgettable weekend escapes.

Fire Nightclub

1.3 km

Vauxhall's railway arch behemoth: all-night house marathons, go-go dancers, and dawn-defying beats in London's gay club epicenter.

Heaven

1.4 km

London’s iconic gay superclub under the railway arches — big nights, loud music, drag, and late finishes in the heart of the West End.

Ministry of Sound

1.4 km

London's legendary dance music cathedral since 1991, where world-class sound systems and global DJs fuel euphoric nights across four pulsing rooms.

TSQ Club

1.5 km

Dive into Trafalgar Square's nightlife pulse at TSQ Club, where eclectic beats, dazzling lights, and craft cocktails fuel unforgettable weekend nights in London's heart.

Corsica Studios

1.5 km

Experience London’s underground music pulse at Corsica Studios, where intimate vibes meet exceptional sound beneath historic railway arches.

Proud Late

1.6 km

Dive into two-storey glamour under Waterloo Bridge: cabaret acrobatics, burlesque dazzle, supper feasts, and non-stop clubbing till 5am in London's West End nightlife epicenter.

The Scotch of St James

1.8 km

Legendary Mayfair speakeasy where 60s rock stars jammed and today's elite dance till dawn in velvet-clad intimacy.

Tiger Tiger London

1.8 km

Experience London’s iconic Haymarket nightclub with six vibrant rooms, lively DJs, and a dynamic party atmosphere just moments from Piccadilly Circus.

For the vibe & atmosphere seeker

- Historic

- Unique

- Scenic

For the design and aesthetic lover

- Vintage Styles

- Rustic Designs

- Art Deco Styles

For the architecture buff

- Historic

- Landmarks

- Heritage Neighborhoods

For the view chaser and sunset hunter

- Iconic Views

- Waterfront

For the social media creator & influencer

- Architectural Shots

- Photo Spots

For the eco-conscious traveler

- Sustainable

- Eco-Friendly

- Protected Area

For the kind of experience you’re after

- Cultural Heritage

- Myth & Legends

- Day Trip

For how adventurous you want the journey to be

- Easy Access

Location Audience

- Family Friendly

- Senior Friendly

- Solo Friendly

- Couple Friendly